RESEARCH

YOU CAN DONATE TO SUPPORT OUR RESEARCH ON MENTAL HEALTH AND EMOTIONS HERE.

Emotions are powerful processes that enable us to respond adaptively to life’s triumphs and challenges and a longstanding assumption has been that positive emotions are predominantly adaptive relative to negative emotions. Further, when emotional responses go awry, they can result in substantial distress and impairment and–consistent with the above-stated assumption–this has been studied largely with regard to negative emotions. The PEP Lab's research program has sought to shift these theoretical and empirical tides to illuminate the nature of, and mechanisms underlying, positive emotion disturbance and its risk for psychopathology onset and severity. Growing work indeed suggests that disturbances in positive emotional processes are a major factor in the onset and maintenance of severe and chronic psychological disorders (e.g., Gruber et al., 2011; 2019; 2023). We study these topics in at-risk and diagnosed mood-disordered and healthy adolescents and adults using experiential, behavioral, peripheral psychophysiological, and neurocognitive tools. We have recently expanded our scope of work to include large-scale, longitudinal, and multi-site surveys and experience-sampling approaches outside of the laboratory to investigate affective predictors of mood health in emerging adults. Furthermore, we have expanded the inclusivity and cross-cultural diversity of our work, including focusing on historically marginalized (e.g., Latinx/e) young adults and cross-cultural collaborative work with young adults in India and Brazil. More details are below.

Positive Emotion Dysregulation Across Disorders

Are problematic positive emotion responses evident across disorders? Understanding the role that positive emotion plays in psychological disorders is relevant for elucidating the ways in which emotions may be compromised, identifying areas of resilience, and developing interventions aimed at targeting positive emotional difficulties (e.g., Gruber et al., in press; Gruber et al., 2023; Gruber, 2019; Gruber, 2011; Gruber & Moskowitz, 2014; Villanueva, Silton, Heller, Barch & Gruber, 2021). One route we're taking is to adopt transdiagnostic approach to understand the contribution of disrupted positive emotion to mental health outcomes across a variety of populations. Examples include:

Positive Emotions and Psychological Disorders

An ideal point of entry to begin to understand how positive emotion can go awry is through the study of people with a history of mania, or bipolar disorder (BD). This work focused on a novel perspective of positive emotion disturbance (Positive Emotion Persistence or PEP; e.g., Gruber et al., 2008; Gruber, Harvey & Johnson, 2009; Gruber, 2011 and explored this model in individuals at risk for, or with a lived history of, mania or bipolar disorder (BD). The central thesis guiding PEP is that bipolar disorders are associated with heightened magnitude of positive emotion responses that are context insensitive (i.e., persist across contexts. Of import, in our work positive emotion responses among BD-relevant populations persist across both individual experimental (i.e., film clips) and more naturalistic and socially embedded (i.e., empathic accuracy, dyadic interaction) paradigms (Gruber et al., 2011; 2019; Devlin et al., 2016; Dutra et al., 2014). Since tenure, my research program’s next stages have examined theoretically-motivated processes supporting the elicitation of positive emotions (driving processes) and those that foster the persistence of positive emotions over time (maintaining processes) among BD-relevant individuals (e.g., Gruber et al., 2023). One theme of our lab’s work has focused on isolating regulatory processes underlying emotion regulation challenges observed within BD and more generally (Preece et al., 2021; Villanueva, Swerdlow, & Gruber, in press; Villanueva, Silton, Heller, Barch, & Gruber, 2021). We have also examined positive emotion experiences work in individuals with depression, anxiety, and psychosis related experiences

Show Details »

Dark and Light Sides of Happiness and Positivity

The longstanding assumption has been that positive emotions and associated feelings are entirely adaptive. As a result, less scientific attention has been devoted to understanding the ways in which positive emotions might also be a source of dysfunction for our psychological health (Gruber & Moskowitz, 2014).Emerging findings also suggest maladaptive risk-taking, cognitive, and social and mental impairment associated with positive emotion (Gruber, Mauss, & Tamir, 2011). Indeed, the empirical tides have recently begun to change and with it a new wave of research centrally driven by the PEP has pointed to ways in which positive emotionality is also related to a range of poor health outcomes and maladaptive clinical syndromes. Work in the PEP lab is centrally focused on unpacking the nature of positive emotion disturbance by highlighting key themes deterring the ways positive emotion may go awry (e.g. Gruber & Purcell, 2014). These insights are aimed at providing an integrative model for understanding positive emotion as well as how to harness and cultivate appropriate positive feelings. Sample conceptual themes of focus include:

Size: Is more positive emotion really better? Aristotelian definitions of emotional health argue that positive emotions are beneficial up to a moderate degree, but can incur costs when experienced too intensely. In other words, an intensely experienced level of happiness may not convey additional benefits beyond the standard; it may even lead to negative outcomes (for review, see Gruber, Mauss & Tamir, 2011).

Situation: A time and place for positive emotions? Positive emotion has a proper contextual timing, and is not always suited for every situation. Work in clinical populations in the PEP lab suggests that individuals with bipolar disorder who experience positive feelings in inappropriate contexts – such as watching sad films or listening to a distressed partner were at greater risk for developing mania (Gruber Johnson, Oveis, & Keltner, 2008) are at greater risk for psychological disturbance.

Specificity: Not all positive emotions are created equal. Many forms of happiness are associated with adaptive and prosocial outcomes, such as fostering connection to others, altruistic acts, and generosity. But importantly not all specific types of positive emotions appear to promote beneficial outcomes. A more nuanced analysis of different types of positive feelings suggests that some forms may actually be a source of dysfunction. This includes aggressiveness towards others, antisocial behavior, and even an increased risk for the onset of mania (e.g., Gruber & Johnson, 2009). Thus certain kinds of positive emotions – such as those that are too self-focused – may at times hinder our ability to adaptively connect and build bonds with others around us.

Self-regulation: Unable to harness positive emotions? The ability to adaptively regulate emotion has been linked to favorable health outcomes, including greater well-being and social adjustment (Tamir, John, Srivastava, & Gross, 2007) and may sustain, or even improve, mental health outcomes (e.g., Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Tugade & Fredrickson, 2004). By contrast, having little or no self-regulation or control over one’s emotions is associated with maladaptive mental health outcomes, such as increased symptoms of depression and anxiety. Less work has examined consequences of positive emotional experiences perceived as uncontrollable versus controllable. Emerging work generally suggests that controllability over positive emotions – measured both as actively generating or increasing positive emotions as well as decreasing or dampening positive emotions – is associated with beneficial mental health outcomes. By contrast, inappropriately managed positive emotions can incur significant costs on a personal level and within broader social contexts (Gruber, Dutra, Hay & Devlin, 2014).

Stability: Positive emotions best kept stable? A complete understanding of the correlates of positive emotion requires more than an understanding of its overall mean levels but rather, positive emotion can only be fully understood if we account for its dynamics. Thus, examining variation, or stability, in positive emotion is scientifically feasible. Recent research suggests that there is a high variability in positive emotions, ebbing and flowing across the course of several weeks and even causing waves within a single day. Greater oscillations in self-reported positive emotions have been associated with worse psychological health (Gruber, Kogan, Quoidbach, & Mauss, 2014), including lower well-being and life satisfaction and greater depression and anxiety. Thus, too much variability and not enough stability in one’s positive feelings can be a harbinger of poor mental health outcomes.

Striving: Seeking positive emotions may lead to decreased well-being. Not surprisingly, most people want to be feel positive or happy. Recent work by PEP lab and colleagues suggests that striving for positive emotions may actually cause more harm than good (e.g., Mauss, Tamir, Anderson, & Savino, 2011; Ford, Mauss, & Gruber, in press). Specifically, the pursuit of happiness is associated with problematic clinical health outcomes can be associated with the pursuit of happiness, which also serves as a marker of individuals with a history of depression (Ford, Shallcross, Mauss, Floerke, & Gruber, in press). These findings are consistent with early observations by philosophers who observed that the pursuit of happiness does not always appear to lead to the desired outcomes. In fact, at times, the more people pursue happiness the less they seem to be able to obtain it.

Research Facilities

The PEP laboratory houses space located in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Colorado, Boulder. This space includes a main research laboratory in the Muenzinger Hall building on the main campus which houses psychophysiological equipment and audiovisual capabilities. Additional laboratory space with two additional rooms designated for clinical interviewing, testing and research is located at the Center for Innovation and Creativity (CINC) which also houses the MRI Center. This includes single-participant psychophysiological testing rooms, dyadic clinical interviewing and psychophysiological room, dedicated workstations for students, central control room, and additional lab-designated testing and clinical interviewing rooms at the CINC fMRI Center.

Psychophysiology: Psychophysiology testing stations are each equipped with Mindware, Inc. multi-channel chassis device (Mindware Technologies, Gahanna, OH) that record continuous data analyzed offline via MindWare or AcqKnowledge software. A TTL digital signal automatically enables the synchronization of physiological data with the onset of the different experimental periods and observational data. This allows for the measurement of a number of physiological responses of the autonomic nervous system especially important to emotional responding, including eletrocardiograph (e.g., heart rate, interbeat-interval, heart rate variability, respiratory sinus arrhythmia), vascular impedance (e.g., pre-ejection period, cardiac output, stroke volume), electrodermal (e.g., skin conductance level and response rate), respiratory (e.g., respiratory frequency, respiratory depth), finger pulse (e.g. finger pulse transit time and amplitude), skin temperature, and blood pressure.

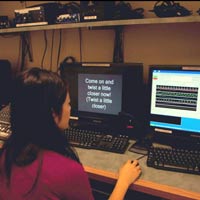

Behavioral Observation & Coding: The PEP laboratory is equipped with audio-visual technologies for clinical interviewing and behavioral observation of experiments. Testing rooms contain a mounted digital camera to monitor participants and collect high-resolution digital video recordings. These video recordings are synchronized with continuous psychophysiological responses and behavioral expressions that can be coded offline using Noldus Behavior Coding Software. The behavioral testing rooms include mounted digital cameras to discretely monitor participants and collect digital video recordings during clinical interviews and baseline laboratory PEP assessments. These video recordings are synchronized with continuous psychophysiological responses using Noldus Behavior Coding Software and are coded for behavioral expressivity of emotion using the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). Computers in the control room deliver stimuli in behavioral experiments to participants via E-Prime (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.), Matlab (Mathworks), and Medialab (Empirsoft), and DirectRT (Empirisoft) software.

Functional Neuroimaging and Neurophysiology: Work in the PEP lab primarily takes advantage of the scanner at the CINC center. The CINC center is part of the Intermountain Neuroimaging Consortium which promotes collaboration and knowledge-sharing among area neuroscientists, and an offers an unprecedented opportunity for other scientists in the region to enhance their existing research by making use of the CINC's expertise and cutting edge neuroimaging resources. Data analysis and backup resources (SPM8, FSL, Matlab) are available at the CINC center. Our lab frequently collaborates with faculty both within and outside of CU Boulder to conduct studies examining neurophysiological processes associated with emotion regulation in both at risk and mood-disordered populations.

Eye-tracking: To isolate cognitive processes that may contribute to emotion-related disturbances in adults with and without psychopathology, we have collaborated with other cognitive psychology labs to examine the way people visually attend to events in the world around them shapes their emotional responses. Our previous work has employed eye-tracking technology (which enables identification of patterns of attention-related biases towards, or away from, emotion-laden stimuli) as well as dot probe tasks.

Neuroendocrinology: Our previous collaborative work (with Dr. Pranj Mehta and Keith Welker) has examined hormones such as testosterone and cortisol through saliva to examine how they are linked to reward sensitivity and behavioral indices of emotion regulation. By using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA), a diagnostic technique used to measure salivary hormone concentrations, we have previously examined hormone concentrations throughout the day in a quasi-experience sampling study.

Clinical Assessments: The PEP lab employs clinical assessment techninques including a clinical interviewing room equipped with audiovisual recording, and clinical assessment batteries including the SCID-5, YMRS, CARS-M, BMRS, QIDS-C, LIFE, GAF, MMSE, WAIS, and ShortOMC, among others.